Earning or Losing Inheritance via Behavior: A Survey of Behavior-Based Inheritance Laws as Alternatives to the United States Common Law’s Status-Based Model

Comment

By Donovan Benton*

I. Naughty and Nice Inherit Alike

In only three states would a person convicted of abusing their spouse be statutorily barred from inheriting the victim spouse’s property through intestate succession.[1] This means that in the rest of the common law states—and the District of Columbia—if a victim of spousal abuse dies without a will or other testamentary instrument,[2] their property could pass to their abuser, provided they remained legally married at the time of the victim’s death.[3] In many states, this transfer of property would be statutorily predetermined.[4] Alternatively, some legal systems utilize a behavior-based approach to intestate inheritance applicable to marital, biological, and adoptive relationships alike. In this context, “behavior-based” refers to specific actions an heir may take that would disqualify them from receiving their otherwise statutorily mandated intestate share.

While behavior-based barriers to inheritance already exist in the United States, the overall intestate succession model is largely “status-based.” In a status-based intestate system, an heir inherits based on who they are rather than what they have done,[5] a perplexing system in a society otherwise so committed to the idea that a person is entitled to or earns what they are allowed to possess.[6] This Comment suggests ways in which intestate succession laws may better account for a potential heir’s good or bad conduct via a survey of behavior-based inheritance laws, namely (1) the Uniform Probate Code, (2) existing state laws, (3) an international example from China, and (4) current trends in the probate system. The ultimate solution will require development of a system capable of balancing issues of constitutional and common law doctrine, management of unintended consequences and avoidance of undesired social impact, preservation of judicial expediency and finality, and supplication of an American desire to transmit wealth at death without the probate process.

II. Overview and Underlying Problems of Intestate Succession

Before exploring behavior-based solutions to problems in intestate succession law, an example of the issues created by the current status-based system must be acknowledged. Over fifty years ago in Vermont, Charlotte Mahoney fatally shot her husband, Howard, and was later convicted of manslaughter.[7] The state, loath to let Charlotte receive property from the person she murdered, ordered that Howard’s estate be distributed to his parents.[8] However, Vermont law at the time entitled Charlotte, the spouse of Howard, to her husband’s estate before his parents.[9] Though several other states by that time had enacted statutes that would have prevented Charlotte from receiving any portion of Howard’s estate, Vermont law had no such provision.[10] Charlotte subsequently appealed the unlawful order transferring Howard’s property to his parents, forcing his parents into an intestate succession battle over their murdered son’s property.[11]

Understanding the basics of intestate succession law reveals how the fight over Howard Mahoney’s property became so messy. The phrase “intestate succession” refers to the process by which property passes from a “decedent,” a deceased person, to an “heir,” a person entitled to take property through their state’s intestate succession laws.[12] Intestate succession only occurs when the decedent dies without a valid will directing the disposal of their property.[13] Without explicit instructions found in a decedent’s will, the state applies its succession laws to automatically divvy out the decedent’s property.[14] As many as seventy-five percent of Americans die intestate, therefore leaving the property of hundreds of millions of people to be distributed without regard for the decedent’s actual wishes.[15]

American intestate succession is primarily a formulaic process,[16] considering only degree of relation, or status, between heir and decedent.[17] Typically in American common-law, spouses take first,[18] then any surviving descendants, then any surviving ancestors or collaterals,[19] and if all else fails the estate escheats[20] to the state.[21] While this system intends to replicate what the state presumes the intestate decedent desired for the distribution of their property, little thought is given to the actual quality or nature of the relationships between heirs and decedent when determining rights of inheritance.[22] As a result, situations arise where heirs with little to no relationship with the decedent may nonetheless inherit, or worse, an heir may inherit despite rude, abusive, or possibly even criminal acts committed against the decedent.[23]

In the case of Howard and Charlotte Mahoney, the Supreme Court of Vermont ultimately relied on the doctrine of constructive trust to prevent the unjust enrichment of Charlotte Mahoney.[24] The court balanced two opposed principles, one grounded in legislation, the other in policy: Charlotte could not be stripped of her statutory right to Howard’s estate, but public policy demanded that a “slayer [be] denied any right to benefit from the[ir] wrong.”[25] The Mahoney court’s solution was to vest Howard’s estate in Charlotte but then make her a constructive trustee of the estate for the benefit of Howard’s parents.[26] The court’s seemingly unfair resolution afforded to Howard’s parents exemplifies the problems inherent in intestate succession laws that do not consider the heir’s behavior. What could have been prevented by a long-recognized statutory solution, like those already enacted in many jurisdictions, instead necessitated a lengthy and costly court battle replete with doctrinal manipulations and legal gymnastics.[27] The situation in Vermont present in the Mahoney case remained until 2009,[28] but a national solution to the case’s dilemma arrived only three years later.

III. The Uniform Approach to Modernizing Antiquated Law

American intestate succession law received an overhaul in the mid-twentieth century in the form of provisions granting statutory authority to persons challenging an heir’s receipt of a decedent’s property.[29] Upon a decedent’s death, the administration of an intestate estate begins when an interested person[30] prepares and files an application for probate in their state’s appropriate court.[31] After approving the application, the court will make a determination of heirs based on state law and accordingly issue letters to a personal representative of the estate.[32] The decedent’s estate is then inventoried and appraised, public notice is posted to other interested parties, and creditors are ensured payment.[33] The administrator completes the succession by providing an accounting to the court and distributing the remainder of the estate to the heirs.[34] Interested persons may challenge the distribution to a particular party at any time after that party’s identification, but as seen in the Mahoney case, these challenges are not easily won without statutory authority.[35]

Applicable behavior-based intestate succession laws become essential during the court’s determination of heirs, namely, after the filing of the application but before the appointment of an estate administrator, thus removing the need for challenges like that from Howard Mahoney’s parents. In 1969, the Uniform Law Commission published the Uniform Probate Code (UPC) aimed to “simplify and clarify the law concerning the affairs of decedents” and to “promote a speedy and efficient system for liquidating the estate of the decedent and making distribution to the decedent’s successors.”[36] An essential provision of the UPC allowed courts to automatically remove persons who intentionally killed the decedent from considerable heirs.

A. The Slayer Provision: UPC Section 2-803

The 1969 version of the UPC contained a behavior-based barrier to intestate inheritance in its Section 2-803 homicide provision: “[a]n individual who feloniously and intentionally kills the decedent forfeits all benefits under this [article] with respect to the decedent’s estate, including an intestate share. . . . If the decedent died intestate, the decedent’s intestate estate passes as if the killer disclaimed the intestate share.”[37] Under this provision, any potential heir who slays the decedent cannot inherit from that decedent through intestate succession.[38] The provision not only applies to heirs who personally kill the decedent but also reaches perpetrators acting as an “accomplice or co-conspirator” to the killing.[39]

Importantly, Section 2-803’s drafters distinguished between criminal and civil liability for intentional homicide.[40] While criminal liability sufficed to activate Section 2-803, it was not necessary for triggering the slayer provision.[41] This version of the law tasked the courts with determining whether by a “preponderance of the evidence,” the evidentiary standard most common in civil trials, the killer would have been found liable for the killing, whether or not criminal standards of evidence had been met.[42] The use of a civil-level burden of proof showed that exclusion from inheritance was not meant as a punishment for bad behavior but rather served as an effectuation of the decedent’s presumed intent. In other words, the law presumed that the decedent would not want their intentional killer to inherit their property, no matter the level of criminal culpability.[43] In a comparison between status-based and behavior-based ideas of intestate succession, this rationale serves a crucial role. While statutes barring inheritance by killers may appear as a behavior-based punitive measure, in the common law tradition, such statutes intend to carry out the presumed intent of the decedent.[44]

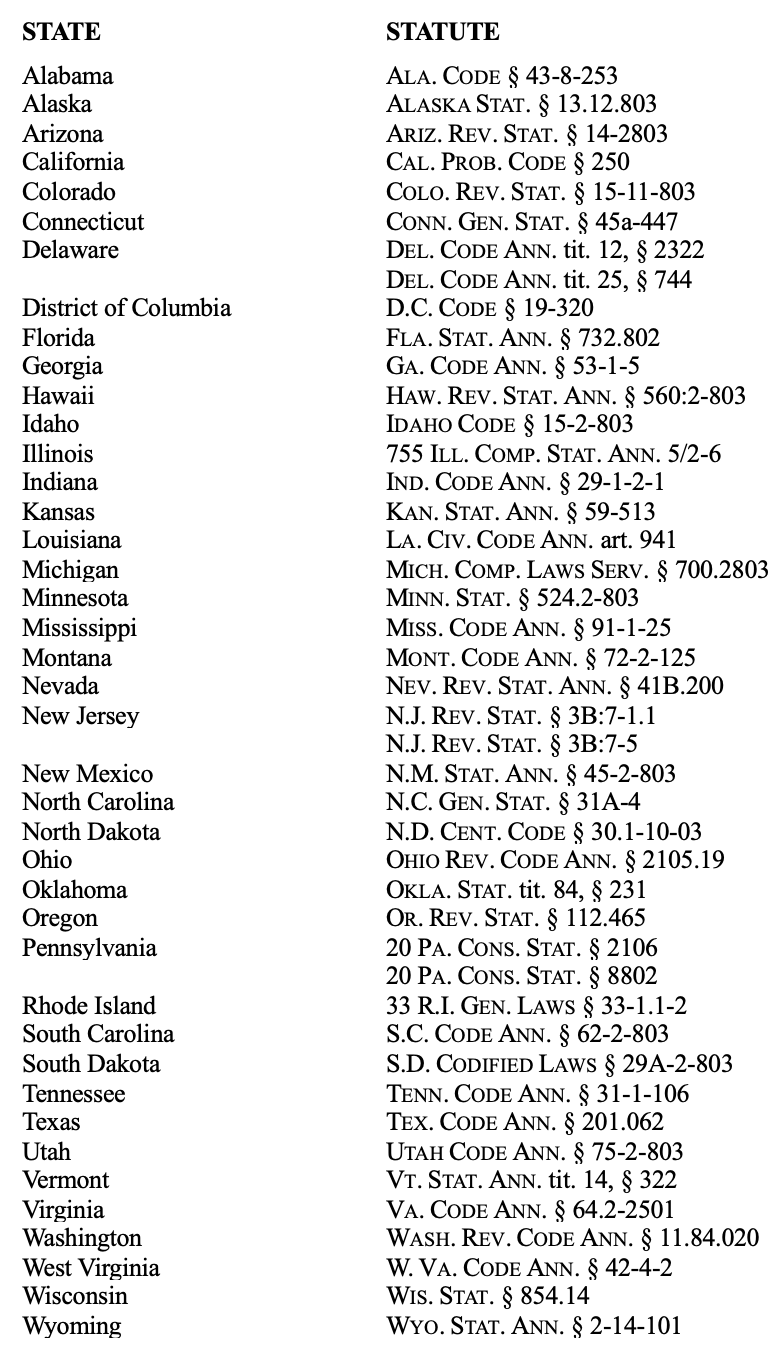

What impact this punitive versus presumed intent distinction may have on the development of behavior-based intestacy law in the United States is difficult to predict, but its importance is likely to recede as time passes. In 1990, the ULA revised Section 2-803 to make its severance from the rest of the UPC more difficult thereby encouraging states adopting the UPC to retain the homicide provision.[45] At present, all but ten states have adopted some form of slayer statute.[46] Currently, of the states with slayer provisions, eleven use the 1990 version of UPC Section 2-803,[47] six use the original 1969 version of UPC Section 2-803,[48] and the remaining twenty-three use their own versions of slayer statutes.[49]

B. The Unworthy Parent Provision: UPC Section 2-114

In 1990, the Uniform Law Commission significantly revised Article II of the UPC.[50] Both a societal “decline of formalism in favor of intent serving policies” and the “advent of the multiple-marriage society,” wherein Americans divorce and remarrying different partners, guided the Commission to these revisions.[51] Thus, because a “significant fraction” of the population married multiple times, the UPC’s provisions needed to account for “stepchildren and children by previous marriages.”[52] These considerations resulted in the UPC Section 2-114, titled “Parent Barred from Inheriting in Certain Circumstances.”[53]

While the original Section 2-114 focused primarily on fathers’ failures to recognize illegitimate children, revisions in 2008—and the provision’s current language—expanded its coverage by adopting language barring inheritance “on the basis of nonsupport, abandonment, abuse, neglect, or other actions or inactions of the parent toward the child.”[54] This provision now tasks courts with establishing through “clear and convincing evidence that immediately before the child’s death the parental rights of the parent could have been terminated” under the laws of their respective states.[55]

Subsections (b) and (c) provide additional details relevant to the behavior versus status-based distinction. Section 2-114(b), which reads “a parent who is barred from inheriting under this section is deemed to have predeceased the child,” prevents only the offending actor (the “bad” parent) from inheriting while retaining inheritance by lineal descendants or ancestors of that actor.[56] Section 2-114(c) further provides that “the termination of a parent’s parental rights to a child has no effect on the right of the child or a descendant of the child to inherit from or through the parent.”[57] Together, these two subsections limit the negative consequences of the parent’s actions to that “bad” parent alone. However, these provisions arguably still fail to reconcile “presumed intent” with actual intent.[58] For example, a decedent child may not wish for other descendants of the parent who abandoned them to inherit their property. Therefore, while UPC Section 2-114 represents a step towards behavior-based inheritance law, its language can permit results contrary to a decedent’s actual intent.[59]

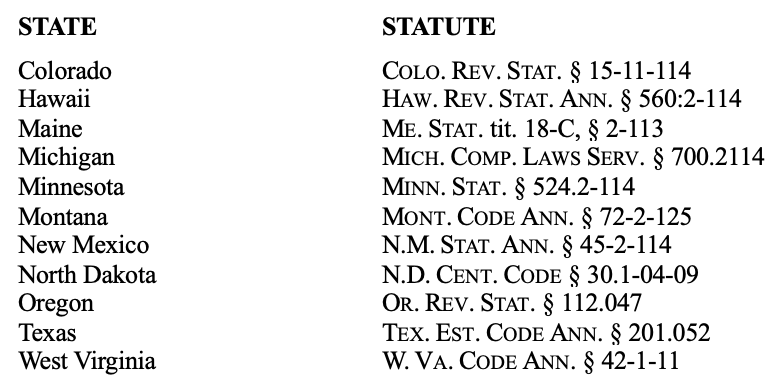

The UPC’s provision barring inheritance by unworthy parents is less popular than its slayer provision. Whereas forty states enforce slayer statutes,[60] only thirty-two states impose statutes barring inheritance as a result of some form of parental deficiency.[61] Of the thirty-two states that have such statutes, only eleven of them contain substantial similarities to UPC Section 2-114.[62] Instead, twenty-one states rely on nonuniform statutes that establish methods by which a parent may demonstrate their ability to inherit from a nonmarital intestate child.[63] These methods include actions such as the parent acknowledging parentage in writing,[64] engaging in an open and notorious parent-child relationship,[65] providing financial support,[66] or consistently paying child support.[67]

IV. Going Beyond the Uniform Approach

Statutes preventing slayers and unworthy parents from inheriting from their decedent victims, like UPC 2-803 and 2-114, represent a respectable first step toward a behavior-based intestate succession model. Ending here, however, would assume homicide and parental neglect as the only two reasons a decedent would want heirs to be excluded from property distribution. Both domestic and foreign jurisdictions, however, provide additional reasons to exclude undeserving heirs from inheritance. Thus, this section provides an overview of domestic statutes going beyond the subject matter addressed by the UPC, as well as an international system distinct from the American approach.

A. Beyond Slayers and Unworthy Parents

Several states exceed the provisions suggested by the UPC and provide additional bars to inheritance in consequence of certain targeted behaviors.[68] These states’ provisions serve as examples for a more expansive statutory scheme like the UPC and serve as blueprints for an increasingly behavior-based intestate succession model in the United States.

1. Maltreatment of Vulnerable Adults

Maltreatment of vulnerable adults constitutes a particular class of conduct that prohibits potential heirs from inheriting.[69] For example, Connecticut law provides that a family member proven guilty of abuse in the first degree “shall not inherit or receive any part of the estate of the deceased victim . . . relating to intestate succession.”[70] “[A]buse in the first degree” is defined as the intentional “abuse of an elderly, blind or disabled person or a person with intellectual disability” that results in “serious physical injury.”[71] This type of abuse consists of any “repeated act or omission that causes . . . serious physical injury,” and “repeated” denotes “that [act or omission] occurs on two or more occasions.”[72] California, Michigan, and Oklahoma also bar inheritance by heirs convicted of abuse, neglect, or exploitation of the decedent.[73]

Illinois law similarly prohibits inheritance by “[p]ersons convicted of . . . abuse[ ] or neglect of an elderly person or a person with a disability,”[74] but adds another barrier to persons convicted of financially exploiting the decedent.[75] Montana law prohibits only financial exploitation of vulnerable adults,[76] but unlike Illinois, defines “financial exploitation” as:

The act of purposely or knowingly standing in a position of trust and confidence with a vulnerable adult and obtaining, using, or attempting to obtain or use at least $1,000, whether in one or more acts, of a vulnerable adult’s money, assets, or property the intent to temporarily or permanently deprive the vulnerable adult of the use, benefit, or possession of the money, assets, or property or to benefit someone other than the vulnerable adult.[77]

Additionally, Oregon and Washington extend their comprehensive statutory prohibitions to reach beyond elderly or disabled victims. Washington provides that “[n]o . . . abuser shall in any way acquire any property or receive any benefit as the result of the death of the decedent.”[78] Oregon similarly forbids “an abuser of the decedent” from inheriting[79] which also applies to abusers of other heirs of a decedent when trying to inherit through those heirs.[80]

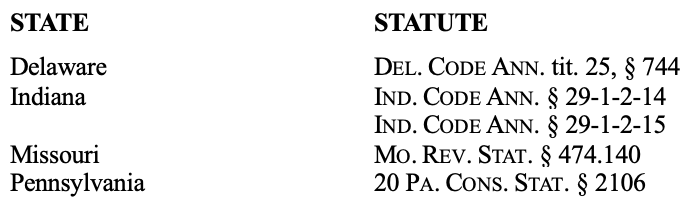

2. Spousal Misconduct

Several states currently utilize intestate succession laws to discourage certain conduct between spouses.[81] Indiana law contains two such statutes, one blocking inheritance by an adulterous spouse,[82] the other barring inheritance by a spouse who abandoned the other.[83] Missouri enacted similar prohibitions within a single statute,[84] but its laws provide that the wayward spouse may regain their inheritance via “voluntarily reconcile[iation]” and “resum[ing] cohabitation” with the faithful spouse.[85] Pennsylvania law states that “[a] spouse who . . . has willfully neglected or refused to perform the duty to support the other spouse, or who . . . has willfully and maliciously deserted the other spouse, shall have no right or interest . . . in the real or personal estate of the other spouse.”[86] Delaware’s spousal misconduct statute explicitly—and anachronistically—applies only to husbands:

If a husband leaves his wife to go with an adulteress or willingly lives in adultery in a state of separation from his wife, not occasioned by her fault, in either case, unless his wife is reconciled to him and suffers him to dwell with her . . . he shall forfeit . . . all demands, as her husband, upon her real or personal estate.[87]

While adultery does not rise to the level of murder in criminal law, it receives equal status to homicide in terms of the presumed intent of the decedent, namely that it is presumed that the decedent would not intend to give to an adulterous spouse, in behavior-based inheritance laws.

3. Other Miscellaneous Statutory Forfeitures of Inheritance

A few states prevent potential heirs from inheriting from a decedent as a consequence of sexual assault and related conduct via legislation.[88] For example, Ohio law provides that “[t]he parent, or a relative of the parent, of a child who was conceived as the result of the parent’s [commission] of [rape][89] or [sexual battery][90] shall not inherit the real property, personal property, or inheritance of the child or the child’s lineal descendants.”[91] A similar statute in Vermont simply stipulates that “[a] parent shall not inherit from a child conceived of sexual assault.”[92] Pennsylvania law prohibits a sexual abuser of a child from inheriting from that child but also adds endangerment and concealment of death of a child to the list of disqualifiers.[93] Texas law expands these limitations to include a host of crimes barring a parent from inheriting from the child’s estate.[94] These Texas statutes incorporate the following offenses as grounds for disinheritance: indecency with a child, assault, sexual assault, aggravated assault, aggravated sexual assault, injury to a child, abandoning or endangering a child, prohibited sexual conduct with a child, and sexual performance by a child.[95]

Rounding out the list of behavior-based intestate succession laws are several uniquely employed statutes from various states. Connecticut law provides that “[a] person finally adjudged guilty, either as the principal or accessory . . . of [first or second degree larceny][96] shall not inherit or receive any part of the estate of the deceased victim.”[97] A Maryland law targets incest, requiring that a parent is not entitled to a distribution of a child’s estate in certain circumstances and if the other parent is also a child of the parent being disinherited.[98] Lastly, Texas law prohibits inheritance by persons convicted of possession or promotion of child pornography where the decedent was the object of the illicit material.[99]

Clearly, many states now enforce their own behavior-based intestate succession laws that exceed the UPC’s slayer and unworthy parent statutes. While there still exists nothing near a uniform national scheme, it is evident that the American statutory soil can support such statutes. The yield, however, is still quite disappointing.

B. China’s Example of Behavior-Based Intestate Succession

But what about an entirely behavior-based model of intestate succession? China employs a dramatically different approach to the American status-based model of intestate succession, and exemplifies the extent to which a behavior-based system may go.[100] Similar to intestate law in the United States, China’s system bars inheritance as a result of reprehensible conduct such as killing, abandonment, maltreatment, and failure to support the decedent.[101] However, unlike in the United States, Chinese law also targets behaviors like infringement on the lifetime wishes of the decedent, misappropriation of estate property, obstruction of disposition of the estate, and murder of another heir.[102]

In addition to a “slayer rule” like that of the American system, the Chinese system also provides that an heir’s killing of another heir in conflict over the decedent’s estate would render that heir unworthy to inherit.[103] Additionally, the Chinese system penalizes potential heirs for abandoning or mistreating the decedent and for attempting to forge, tamper with, or destroy a decedent’s testamentary instrument.[104] Chinese courts may discretionally reduce intestate shares for an heir’s inaction in cases where an heir who had the ability to care for the decedent chose not to.[105] To implement the punitive measures, Chinese courts consider the “duration, means, outcome, and societal impact of an heir’s actions to determine whether those actions satisf[ied] the serious circumstances standard” for unworthiness.[106]

However, unlike intestacy law in the United States, China’s behavior-based intestacy model also seeks to reward “good” behavior.[107] The court, for example, may either readjust intestate shares for existing heirs or elevate stepchildren, stepparents, and stepsiblings to heir status.[108] It even addresses the possibility for non-heirs to “inherit” through the court’s authorization to “distribute an appropriate amount of the estate to any person who is not an heir but provided considerable support to the decedent.”[109] Heirs and potential, inheriting non-heirs may demonstrate good behavior through “contributions to the decedent’s financial, physical, or emotional well-being during [the decedent’s] life, as well as funeral arrangements and expenses after the decedent’s death.”[110] Thus, Chinese courts possess significant discretion in implementing this system of succession.[111]

A version of “forced heirship”[112] in Chinese intestate succession law further illustrates the country’s focus on supporting the needs of the surviving family.[113] China’s forced heirship works to ensure that “qualifying heirs, typically children of the decedent, should receive a ‘necessary portion’ of the estate if they are ‘unable to work’ with ‘no source of income.’”[114] A system of “family maintenance” also allows “aggrieved claimants” to petition for a share of the decedent’s property whether they were a “family member, neighbor, or friend” so long as they “reasonably relied on the support of the decedent prior to their passing.”[115]

By not only penalizing bad behavior but also rewarding “exemplary” behavior, China’s behavior-based system of inheritance is designed to both discourage misconduct and incentivize “private mechanisms of support.”[116] China’s intestate succession model rewarding community support structures serves to balance social and economic reforms that otherwise encourage Chinese citizens to pursue individualized means of wealth generation.[117] The Chinese system better adapts to the evolution of traditional family relationships by granting courts discretion to address the “full range of misconduct” exhibited by heirs toward the decedent.[118]

Nonetheless, the inefficiencies of the Chinese system lay bare: the burden imposed on courts as fact-finders and the necessarily complicated case-by-case distribution analyses results in a judicially-intensive process.[119] The baseline evidentiary standards of China’s system are relatively easy to meet for decedents who spent their entire life in one location, likely with only one set of social relationships and one home.[120] Yet, as social and geographical mobility increases in China, courts will face the more difficult task of tracking down a decedent’s assets through multiple jurisdictions and through several iterations of social relationships.[121] The status-based system of the United States, on the other hand, offers a more predictable and efficient process.[122]

The Chinese system’s principle of providing for the underprivileged through inheritance laws is also fundamentally incompatible with the American system’s principle of testamentary freedom.[123] Therefore, any attempt to institute a behavior-based inheritance model in the United States would succeed only if implemented in a deliberate, prudent manner that preserved acceptable levels of efficiency and predictability for courts and maintained sufficient levels of freedom for testators.

V. What Not To Do in Behavior-Based Intestate Succession

Legislators in the United States must overcome a multitude of hurdles in order to transform status-based intestate succession into a behavior-based model. This section will next address these distinct challenges. First, fundamental constitutional and common law principles must be met. Then, one must compare statutes as-written with statutes as-applied. Lastly, the general shift of American wealth transmission at death away from the probate process must be considered.

A. Violating the Constitution and the Common Law

The United States Constitution prohibits Congress and the states from passing bills of attainder.[124] A bill of attainder is a legislative act that works to inflict punishment on specific people or groups of people without judicial process.[125] Therefore, no proposed behavior-based intestate succession statute may work to punish heirs suspected of certain acts without prior adjudication.[126]

UPC Section 2-803 avoids classification as a bill of attainder by providing specific means which courts may “conclusively” establish that the heir in question was the decedent’s killer.[127] Accordingly, the probate court may simply adopt the previous judgment sua sponte in cases involving a prior “judgment of conviction establishing criminal accountability” for an heir’s intentional killing of a decedent.[128] Alternatively, in the absence of a prior conviction, an “interested person” may ask the court during its determination of heirs to decide whether under the “preponderance of the evidence” standard the potential heir in question “would be found criminally accountable” for the intentional killing of the decedent.[129] If the court so finds, its conclusion is sufficient for UPC Section 2-803’s application and the potential heir is excluded from succession.[130] Similarly, UPC Section 2-114 allows probate courts to adopt any previous judicial termination of parental rights, or to consider “clear and convincing evidence” that parental rights could have been terminated “immediately before the child’s death.”[131] Therefore, future statutes intending to regulate the behaviors of potential heirs should adopt the UPC approach and require prior adjudication and specific evidentiary standards to meet before anyone is excluded from heirship.

Additionally, state constitutions may also provide obstacles to passage of behavior-based intestate succession statutes. The common law concept of “corruption of the blood” prevented people convicted of “treason and other capital offenses” from inheriting property.[132] A related concept called “forfeiture” allowed the king specifically to retake land from a tenant guilty of treason.[133] These ideas never gained popularity in the United States, and several state constitutions expressly require that “no conviction of crime shall [constitute] corruption of blood or [cause] forfeiture of estate.”[134] More generally, a presumption against forfeitures wherein courts deciding property ownership adopt interpretations of relevant language least likely to result in loss of property by the current interest holder developed in American succession law.[135] Therefore, behavior-based barriers to intestate inheritance must avoid semblances of the disfavored common law doctrines of corruption of the blood and forfeiture of estate.

Slayer statutes, like UPC Section 2-803, avoid these risks by depriving the slayer of the “expectancy interest[,]” that operates to create the inheritance in the first place.[136] Importantly, deprivation becomes an unconstitutional forfeiture of property only when courts deprive the slayer of the decedent’s estate in the absence of statutory authority.[137] Statutory authority, such as a slayer statute, transforms the situation from one in which the potential heir suffers deprivation into one in which the potential heir is not unjustly enriched.[138] Similarly, statutes like UPC Section 2-114 first require that parental rights were or could have been judicially terminated, therefore determining that the potential heir has no property interest they can be deprived of in the first place.[139] This explains why current laws often include language that suggests the barred heir is “deemed to have predeceased” the decedent.[140] Thereby, the rights of predeceased individuals to a decedent’s property are essentially terminated.[141]

A future behavior-based barrier to intestate succession must therefore contain two parts. First, it must create a predicate termination of any right a potential heir would have had to a decedent’s property. Second, it must create the means by which courts determine the applicability of the predicate termination to a potential heir to ensure there is no unconstitutional deprivation of property.

B. Accidentally Punishing Incapacity

By the mid-1990s, states commenced enacting statutes akin to UPC Section 2-114, better known as “Termination of Parental Rights” (TPR) statutes.[142] The intended premise of these statutes are that in order for a parent’s parental rights to be terminated, the parent must be “bad” and therefore undeserving of any benefits derived from the child.[143] In practice, however, TPR statutes unintentionally punish parents on the basis of incapacity instead of iniquity.[144]

For example, in an Indiana case, the court terminated parental rights due to the parents’ inability to financially provide for their premature and disabled child.[145] Doctors diagnosed the mother and father of the child “as mildly [intellectually disabled] with I.Q.’s of 64 and 62, respectively.”[146] Consequently, the state placed the child, “born five weeks premature” and “on a sleep apnea monitor and oxygen support from age six weeks through eighteen months” into foster care while the parents participated in a state-designed parental “counseling and training” program.[147] Even before completion of their training program, the court agreed with the state that the parents “lacked the skills and knowledge necessary to fulfill the obligations of a parent to a child with the specialized needs” and that termination of their parental rights was in the child’s best interests.[148] An applicable TPR statute consequently terminated any interest the parents would have had in their child’s estate should she predecease them.[149]

In Minnesota, a TRP statute terminated two parents’ rights to inherit from their children when a court determined the parents as “palpably unfit to parent” their four children.[150] In this case, the father suffered permanent brain damage when he fell off a roof during a work accident, while the mother suffered from “low cognitive functioning and a personality disorder.”[151] After incidents of domestic violence and an unsuccessful attempt to complete a reunification program with their children, the court determined that “both parents simply ha[d] no capacity to parent or to engage in constructive efforts to improve their ability to parent.”[152] Through operation of the state’s TPR statute, the parents lost the right to inherit from their children because of their “mental conditions, not because of conduct towards the children.”[153] As such, if TPR statutes primarily mean to punish “bad” parents, they also tend to be over-inclusive in their implementation.[154]

Importantly, then, in such cases TPR statutes punish “the inability of the parents to perform adequately as parents, rather than . . . any morally reprehensible behavior by the parents.”[155] When well-meaning parents demonstrate an inability to adequately care for their child, termination of the parent-child legal relationship may, standing alone, further the welfare of the child.[156] However, tying automatic termination of inheritance rights to such a basis seems particularly cruel and also misses the mark if the goal is encouragement of good decision-making by potential heirs with respect to potential decedents. Future authors of behavior-based intestacy statutes must therefore be careful to ensure the intent behind the legislation survives the transition from law as-written to law as-applied.

C. Avoiding Probate: Only Lawyers Want to Go to Court

Currently, American succession law trends away from probate transfers, creating a final hurdle for a behavior-based succession statute to overcome. By the 1980s, the law of succession underwent a “nonprobate revolution.”[157] The revolution consisted of free market, noncourt modes of property transfer absent probate or wills.[158] The primary beneficiaries of the probate system, creditors, divested themselves of reliance on court intervention to collect decedents’ debts.[159] Additionally, courts generally “sympathize[d] with people who want[ed] to avoid probate.”[160] Perceptions of the probate process as “costly, slow, and cumbersome” led to the development of “will substitutes” by which testators could “achieve the practical effect of a will . . . outside the probate system.”[161] Through various jurisprudential manipulations, courts transformed testamentary transfers of property into inter vivos transfers[162] to “avoid conflict with the probate monopoly theory of wealth transmission on death.”[163] Court decisions upholding will substitutes signaled “judicial approval” of these nonprobate techniques as “reliable, efficient, and socially useful alternatives” to testamentary wealth transmission.[164]

In short, courts, creditors, and beneficiaries sought to avoid judicial intervention in testamentary wealth transfers.[165] The changes resulting from the nonprobate revolution remain today. In this climate, it is possible that by the time of the execution of all nonprobate instruments, the decedent may have no assets left for probate. However, behavior-based intestate succession statutes will still remain valuable in such a system. Where estate assets remain, and where no testamentary device disposes of them, statutes barring inheritance by bad-behaving heirs would still have full effect.

VI. What To Do in Behavior-Based Intestate Succession

Present United States legislation proves an initial movement towards behavior-based intestate succession. The original UPC suggested provisions barring slayers from inheriting from their victims, and the 1990 revision added unworthy parents to the list of barred heirs.[166] Following suit, individual states then enacted statutes barring inheritance for maltreatment of vulnerable adults, spousal misconduct, sexual assault, and property crime.[167] To continue the movement, American observers may turn to the Chinese example of an entire behavior-based intestate succession model.[168] Unfortunately, various substantive and empirical hurdles limit further progress: constitutional prohibitions and common law doctrines against deprivation of property rights; unintended consequences of statutes creating undesired social impact; observed inefficiencies and manipulations in the Chinese succession model; and an American desire to transmit wealth at death without the probate process.[169]

While full adoption in the United States is farfetched, piecemeal adoption of key individual provisions may be successful and impactful. To be operable, these behavior-based intestate succession provisions will need to possess several competing characteristics. First, they must not run afoul of fundamental common law and constitutional principles: no bills of attainder and no denials of recognized property rights.[170] For example, if Tommy Taker stole for years from what was to become Grandma Giver’s intestate estate, one might reasonably believe Tommy should receive a reduced portion—or none at all—upon Grandma’s death. However, without any statutorily defined process for adjudicating Tommy’s guilt, there can be no deprivation of what property rights are defined by his state’s succession scheme. And further depending on the state, the barring statute may also have to be written such that Tommy is only deprived of an expectancy interest in Grandma’s estate in order to avoid an unconstitutional deprivation of a vested property interest.[171]

Second, behavior-based succession statutes must actually, and only, address the class of conduct they intend to regulate.[172] Undoubtedly, states did not intend for TPR statutes to penalize victims of domestic abuse, yet as applied they have had exactly that effect.[173] Legislators have two options for avoiding the TPR problem. First, they must use precise language such that the statute may not feasibly be applied to any persons or conduct other than those targeted by the statute. Or second, the statute must expressly allow judicial discretion sufficient to ensure the statute is not misapplied. It may be perfectly sensible for termination of the parent-child relationship where a minor child’s one surviving parent, for example, indeterminably lives in a comatose state due to a serious accident involving the entire family. However, a TPR statute like UPC Section 2-114 would also likely terminate the surviving parent’s right to the child’s estate if he or she also died as a result of the accident on the basis of “nonsupport.”[174] In actuality, the parent failed to support the child because they were literally unconscious, yet the statute penalizes them regardless.[175] In this case, the statute serves no one’s interests and only creates injustice.

And third, behavior-based succession statutes must be operable in a system valuing efficiency and finality.[176] If additional fact-finding and deliberation are required, or if any substantial risk of having to reconsider rendered judgments exists, courts will likely be resistant.[177] If interested parties—creditors in particular—are forced to wait through prolonged judicial application of statutes potentially barring intestate shares, they will further seek to handle matters extrajudicially.[178] Finally, with nonprobate instruments now automating such a significant portion of wealth transfer at death, the remaining probate assets may be of too negligible value[179] for rightful owners to pursue them.[180] For these reasons, behavior-based succession statutes should apply to clearly identifiable classes of people or activities, and be amenable to systematic, mechanical implementation.

VII. Conclusion

Behavior-based intestate succession laws better account for behavior than status-based alternatives. Furthermore, behavior-based laws can both discourage negative and abusive behaviors and encourage beneficial conduct. At present, behavior-based laws in the United States work only to penalize bad behavior because default succession schemes allow heirs to inherit simply by being alive. Future American succession law must better reward good behavior by enacting statutes that elevate supportive, positive conduct toward one another over mere biological happenstance.

Appendix A – “Slayer” Statutes Barring Intestate Inheritance

Appendix B – “Minor Maltreatment” Statutes Barring Intestate Inheritance

Appendix C – “Vulnerable Adult Maltreatment” Statutes Barring Intestate Inheritance

Appendix D – “Termination of Parental Rights” Statutes Barring Intestate Inheritance

Appendix E – “Spousal Misconduct” Statutes Barring Intestate Inheritance

Appendix F – Miscellaneous Statutes Barring Intestate Inheritance

Footnotes:

* J.D. Candidate 2025, Loyola University New Orleans College of Law; M.S. Mining and Mineral Resources Engineering 2013, Southern Illinois University–Carbondale; M.A. History 2009, Southern Illinois University–Carbondale. Special thanks to Professor María Pabón for getting me interested in this topic, Professor Monica Hof Wallace for all of her help and encouragement in writing this Comment, Professor James Étienne Viator for his guidance in the drafting process, and the 2024-2025 Loyola Law Review for the invaluable help in bringing this Comment to life.

[1] These states are Connecticut, Oregon, and Washington. Other states have abuse-related barrier statutes that apply only in specific circumstances. Illinois law bars inheritance only if the victim of the abuse was also elderly or disabled. Oklahoma law prohibits inheritance only if the victims were “vulnerable” adults. And Pennsylvania law prevents inheritance only from child victims of sexual abuse. See infra Appendices B, C.

[2] For the sake of brevity, the term “will” from this point forward in the Comment is inclusive of all testamentary transfer instruments, unless otherwise noted.

[3] Spouses generally stand first in line to inherit from intestate decedents. See Gerry W. Beyer, Wills, Trusts, and Estates 1920 (8th ed. 2023) [hereinafter Beyer]. See also Unif. Prob. Code § 2-102 (Unif. L. Comm’n 2019). Louisiana follows a different scheme. See La. Civ. Code art. 1493. As a general note to the reader, this Comment is a broad survey of American common law intestate succession rather than Louisiana’s succession and donation laws within its civil law system. Therefore, terms common to both legal traditions should be assumed to possess their common law meaning unless otherwise stated.

[4] Restatement (Third) of Property: Wills and Other Donative Transfers § 2.2 (Am. L. Inst. 2011).

[5] See Beyer, supra note 3, at 19-20.

[6] Inheritance stands unique among the various justifications for property ownership in American jurisprudence. See generally Joseph William Singer et. al., Property Law: Rules, Policies, and Practices 95-181 (8th ed. 2022) [hereinafter Singer]. Sovereignty-based justifications rely on the idea that the government should distribute and recognize ownership of property according to sovereign benefit and social need. Id. at 95–126. Labor and investment based justifications posit the idea that property ownership should be granted in compensation for the expended or promised efforts of the owner. Id. at 126–42. Possession-based justifications rely on the owner’s actual possession and beneficial use of the property. Id. at 150–81. And family-based justifications—like child support—rely on the presumed need of the recipients for the property given to them. Id. at 142–47.

[7] In re Estate of Mahoney, 220 A.2d 475, 476 (Vt. 1966).

[8] Id.

[9] Id. at 477 (citing Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 551 (repealed 2009)).

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Beyer, supra note 3, at 3. Intestate succession may also be referred to as “intestacy” or “descent and distribution.” Id. Heirs only come into existence upon a decedent’s death; while the future decedent still lives, future heirs are called “presumptive heirs” or “heirs apparent.” Id.

[13] Id. In intestate succession, the decedent may also be referred to as “the intestate.” Id.

[14] Beyer, supra note 3, at 14.

[15] Id. at 14–17. The reasons why so many people die intestate are varied. Id. They include inability to pay for drafting of a will, perceived lack of property worth putting into a will, reluctance to deal with the subject matter, reluctance to reveal embarrassing information, and general ignorance of the importance or very existence of testamentary succession. Id.

[16] This Comment does not challenge the rightness of the formula in terms of its approximation of majority sentiment in matters of testamentary property distribution. It is rather calling into question the concept of formulaic processes themselves.

[17] Frances H. Foster, Towards a Behavior-Based Model of Inheritance?: The Chinese Experiment, 32 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 77, 79 (1998) [hereinafter Foster]. See also Grayson M.P. McCouch, Probate Law Reform and Nonprobate Transfers, 62 U. Miami L. Rev. 757, 757–66 (2008) [hereinafter McCouch]. See generally Beyer, supra note 3, at 18–35.

[18] Inheritance Rights of Surviving Spouse, Wills.com, (April 2024), https://www.wills.com/articles/Inheritance-RightsOfSurvivingSpouse#:~:text=In%20general%2C%20it%20stands%20that%20the%20spouse%20is,priority%20to%20inherit%20over%20other%20heirs%2C%20as%20well. However, some jurisdictions follow distribution schemes in which children take before spouses. For example, in Louisiana succession law, heirs “twenty-three years of age or younger” or “permanently incapable of taking care of their persons” are guaranteed their share of the decedent’s property before any other takers. La. Civ. Code art. 1493.

[19] Collateral relatives are persons related to the decedent but not in a lineal line. See Beyer, supra note 3, at 3. In other words, collateral relatives descend from an ancestor of the decedent, but their existence was never dependent on the decedent’s existence. Restatement (Third) of Property: Wills and Other Donative Transfers § 8.4 cmt. a. These would be siblings, nieces and nephews, aunts and uncles, and cousins. Beyer, supra note 3, at 3.

[20] The concept “escheat” comes from the common law tradition of the right of lords to regain a tenant’s land if the tenant died without heirs. Richard L. Brown, Undeserving Heirs?- The Case of the “Terminated” Parent, 40 U. Rich. L. Rev. 547, 568 (2006) [hereinafter Brown].

[21] See Beyer, supra note 3, at 18–35. See also Singer, supra note 6, at 755; Mary Elizabeth Morey, Unworthy Heirs: The Slayer Rule and Beyond, 109 Ky. L.J. 787, 788 (2021) [hereinafter Morey]; Restatement (Third) of Property: Wills and Other Donative Transfers § 2.2-2.4.

[22] Brown, supra note 20, at 561. See also Susan N. Gary, We Are Family: The Definition of Parent and Child for Succession Purposes, 34 ACTEC J. 171 (2008).

[23] Foster, supra note 17, at 79–80. See generally See Beyer, supra note 3, at 47–52; Brown, supra note 20, at 547–48.

[24] Mahoney, 220 A.2d at 478–479. See generally Restatement (Third) of the Law: Restitution and Unjust Enrichment § 55; Eric C. Surette, Effect of Killing of Decedent by Heir or Distributee: Effect of absence of specific statute—View that killer takes as constructive trustee, 23 Am. Jur. 2d Descent and Distribution § 43 (2024) [hereinafter Surette]. The phrase “unjust enrichment” here is not to be confused with the civil law “enrichment without cause” described in La. Civ. Code Ann. art. 2298.

[25] Restatement (Third) of Property: Wills and Other Donative Transfers § 8.4. For an explanation of what is meant by the term “slayer,” see infra Section II.A.

[26] Mahoney, 220 A.2d at 478–479.

[27] For the recognition and use of statutes preventing killers from inheriting their victim’s estates, see Eric C. Surette, Effect of Killing of Decedent by Heir or Distributee—Constitutionality of statutes, 23 Am. Jur. 2d Descent and Distribution § 41 (2024); John W. Wade, Acquisition of Property by Wilfully Killing Another—A Statutory Solution, 49 Harv. L. Rev. 715 (1936). For the court battle and complicated legal analysis, see Mahoney, 220 A.2d at 476.

[28] Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 322 (eff. June 1, 2009).

[29] See Unif. Prob. Code art. II pref. note (referencing promulgation of the Uniform Law Commission’s original “Uniform Probate Code” in 1969).

[30] Typically, “interested persons” will have a pecuniary interest in the decedent’s property, whether as an heir or a creditor. See Beyer, supra note 3, at 249–50.

[31] See id. at 249–51. The “appropriate court” will depend on the state, but at a minimum, it must have “both jurisdiction and venue over probate matters.” Id. at 251.

[32] See id. at 251–60. Personal representatives are usually identified and appointed in accordance with state law, typically beginning with the decedent’s surviving spouse or adult children, proceeding all the way to creditors or “other reputable people in the community.” Id. at 253. “Letters” are simply court-issued documents verifying the administrator’s role. Id. at 259–60.

[33] See Beyer, supra note 3, at 260–65.

[34] See id. at 266.

[35] See supra text accompanying notes 7–10 & 24–28.

[36] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-102.

[37] Id. at § 2-803.

[38] Id. at § 2-803 cmt.

[39] Id.

[40] Id. at § 2-803(g).

[41] Id.

[42] Id.

[43] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-803 cmt.; see also Brown, supra note 20, at 559.

[44] See Beyer, supra note 3, at 48–49.

[45] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-803 cmt. (“The pre-1990 version of this section was bracketed to indicate that it may be omitted by an enacting state without difficulty. The revised version omits the brackets because the Joint Editorial Board/Article II Drafting Committee believes that uniformity is desirable on the question.”).

[46] The ten states without slayer statutes are Arkansas, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, and New York. See infra Appendix A.

[47] The eleven states using the revised Section 2-803 are Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Hawaii, Michigan, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wisconsin. See infra Appendix A.

[48] The six states using the original UPC Section 2-803 are Alabama, California, Florida, Minnesota, New Jersey, and South Carolina. See infra Appendix A.

[49] The twenty-three states using their own versions of slayer statutes are Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming. The District of Columbia also has a nonuniform slayer statute. See infra Appendix A.

[50] Unif. Prob. Code art. II pref. note.

[51] Id.

[52] Id. See also Lawrence W. Waggoner, The Multiple-Marriage Society and Spousal Rights Under the Revised Uniform Probate Code, 76 Iowa L. Rev. 223, 223–24 (1991) (stating that data from the time of the formulation of the 1990 UPC revisions indicated that “almost two-thirds of recent first marriages would be likely to disrupt if current levels persist. Further work leads us to suspect that 60% may be closer to the mark.”).

[53] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-114(a).

[54] Id. The 1990 version only barred inheritance by parents for failure to “treat the child as his [or hers].” Id. at § 2-114 cmt.

[55] Id. at § 2-114(a). The reasoning for this provision is described in infra Section V(A).

[56] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-114(b).

[57] Id. at § 2-114(c).

[58] Brown, supra note 20, at 40.

[59] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-114.

[60] Restatement (Third) of Property: Wills and Other Donative Transfers § 8.4 rep. note 1.

[61] Id. at § 2.5 stat. note 2–5.

[62] The eleven states with statutes substantially similar to UPC Section 2-114 are Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Texas, and West Virginia. See infra Appendix D.

[63] The twenty-one states solely using nonuniform statutes prescribing methods for parents to inherit from nonmarital children are Alaska, Arizona, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. See infra Appendix B.

[64] Connecticut and Iowa. See infra Appendix B.

[65] Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Virginia. See infra Appendix B.

[66] Georgia, Mississippi, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. See infra Appendix B.

[67] Tennessee. See infra Appendix B.

[68] See Morey, supra note 21, at 109 (providing an overview of these statutes and their history).

[69] These statutes can be found in California, Connecticut, Illinois, Michigan, Montana, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Washington. See infra Appendix C.

[70] Conn. Gen. Stat. § 45a-447(a)(1) (2024).

[71] Id. at § 53a-321 (defining “[e]lderly person” as “any person who is sixty years of age or older,” and “[d]isabled person” as “any person who is physically disabled”).

[72] Id. at § 53a-320.

[73] Cal. Prob. Code § 259 (2024); Mich. Comp. Laws § 700.2803 (2024); Okla. Stat. tit. 84, § 231 (2024).

[74] 755 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 5/2-6.2(b) (2024).

[75] Id. at 5/2-6.6.

[76] Mont. Code Ann. § 72-2-813(2) (2023). A “vulnerable adult” is defined as “a person who is:

(i) 60 years of age or older;

(ii) functionally, mentally, or physically unable to provide self-care;

(iii) deemed incapacitated . . . ;

(iv) developmentally disabled;

(v) admitted to a facility licensed by the department of public health and human services;

(vi) receiving services from a home health agency or hospice provider;

(vii) receiving services from an individual provider; or

(viii) self-directing care and receiving services from a personal aide for a physical disability.” Id. at § 72-2-813(1)(f).

[77] Id. at § 72-2-813(1)(c).

[78] Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 11.84.020 (2024).

[79] Or. Rev. Stat. § 112.465(1) (2024).

[80] Id. at § 112.465(2).

[81] These statutes can be found in Delaware, Indiana, Missouri, and Pennsylvania. See infra Appendix E. See also Morey, supra note 21, at 793–94, 798.

[82] Ind. Code Ann. § 29-1-2-14 (2024).

[83] Id. at § 29-1-2-15.

[84] Mo. Rev. Stat. § 474.140 (2024).

[85] Id. at § 474.140.

[86] 20 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 2106(a) (2023).

[87] Del. Code Ann. tit. 25, § 744 (2024).

[88] These statutes can be found in Connecticut, Illinois, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. See infra Appendix A.

[89] Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2907.02 (2024).

[90] Id. at § 2907.03.

[91] Id. at § 2105.062.

[92] Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 315(c) (2024). Under this statute, the parent victimized by the assault may motion for the court to award “sole parental rights and responsibilities” to the moving parent and deny “all parent-child contact” with the nonmoving parent. Id. at § 665(f). Reconciliation between the child and disinherited parent seems to be precluded by the statute, which states that “[a]n order issued in accordance with this subdivision shall be permanent and shall not be subject to modification.” Id. at § 665(f).

[93] 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. §§ 4303, 4304, 6312 (2023).

[94] Tex. Code Ann. § 201.062(3) (2023).

[95] Id. at § 201.062(3)(A)-(M).

[96] Conn. Gen. Stat. §§ 53a-122, 53a-123 (2024). Connecticut defines “larceny” as occurring when a person “with intent to deprive another of property or to appropriate the same to himself or a third person, [ ] wrongfully takes, obtains or withholds such property from an owner. Id. at § 53a-119. An extensive, but not exhaustive, list of examples is provided by the statute, and includes such things as embezzlement, extortion, shoplifting, conversion of a motor vehicle, and even library theft and airbag fraud. Id.

[97] Id. at § 45a-447(a)(1).

[98] Md. Code Ann., Est. & Trusts § 3-111 (2023). This statute was enacted in response to a situation involving a child born of a stepfather’s assault of his stepdaughter. Lauralee Strange, Inheritance for the Illegitimate: Children of Rape and the Need for Progressive Intestate Reform in Texas, 5 Tex. Tech. Est. Plan. Com. Prop. L.J. 465, 481 (2013). During a custody dispute following the stepdaughter-mother’s suicide attempt, the state asked the court to transfer custody to the stepdaughter-mother’s relatives instead of the stepfather-father. Id. The court refused because Maryland law at the time required preservation of the father’s rights, inheritance among them, in planning for the child. Id. The Maryland legislature quickly enacted legislation to prevent any further occurrences. Id.

[99] Tex. Code Ann. § 43.26 (2023).

[100] Morey, supra note 21, at 789.

[101] Foster, supra note 17, at 85–86.

[102] Id. at 86–87.

[103] Id. at 87. Attempted homicides also result in disinheritance. Id. at 90.

[104] Id. at 87. The abandonment, maltreatment, or attempts to commit fraud do not need to result in any significant damage to be considered by the court. See also Morey, supra note 21, at 801–02.

[105] Foster, supra note 17, at 99.

[106] Id. at 92 (citation omitted).

[107] Id. at 81–82; Morey, supra note 21, at 800.

[108] See Foster, supra note 17, at 102–09.

[109] Id. at 109 (citation omitted).

[110] Id. at 103–04.

[111] Morey, supra note 21, at 104, 107, 109.

[112] “Forced heirship” or “forced shares” also exists in some United States jurisdictions, particularly in Louisiana’s civil law tradition. Singer, supra note 6, at 718. The concept comes into force when a decedent’s will does exist, and serves to override the decedent’s wishes expressed therein when certain statutorily defined classes of people—children or spouses, for example—are left out of the decedent’s will. Beyer, supra note 3, at 37.

[113] Morey, supra note 21, at 800.

[114] Id. at 800–01 (quoting Ya-Hui Hsu, Should China Adopt Taiwan's Mandatory Share Doctrine?, 29 Penn. St. Int’l L. Rev. 289, 291 (2010)). China’s forced heirship can also overcome a decedent’s testamentary instrument “by placing an indigent heir’s need over both the other heirs’ relational status and the testator’s intent.” Id. at 801.

[115] Id.

[116] Foster, supra note 17, at 125.

[117] Id. at 117-24 (1998).

[118] Morey, supra note 21, at 802; Foster, supra note 17, at 125.

[119] Morey, supra note 21, at 801; Foster, supra note 17, at 117–24 (1998).

[120] Foster, supra note 17, at 124.

[121] Id. at 123-24.

[122] Id. at 120-21.

[123] Morey, supra note 21, at 803.

[124] U.S. Const. art. I, § 9, cl. 3; id. art. I, § 10, cl. 1.

[125] United States v. Lovett, 328 U.S. 303, 315 (1946).

[126] Landgraf v. USI Film Prods., 511 U.S. 244, 266 (1994).

[127] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-803(g).

[128] Id.

[129] Id. (emphasis added). The UPC defines “interested person” as any person “having a property right in or claim against a trust estate or the estate of a decedent, ward, or protected person,” as well as “persons having priority for appointment as personal representative, and other fiduciaries representing interested persons.” Id. at § 1-201(23).

[130] Id. at § 2-803(g).

[131] Id. at § 2-114(a). “Immediately” is not defined by the UPC. See id.

[132] Beyer, 48-49, supra note 3, at 48–49.

[133] Singer, supra note 6, at 759. Use of the land in the act of committing treason does not appear as a requirement for forfeiture. See id.

[134] Surette, supra note 24, at § 37 (citing to cases from Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Tennessee).

[135] Singer, supra note 6, at 777–78.

[136] Surette, supra note 24, at § 41.

[137] Id. (citing to cases from Kansas and West Virginia).

[138] Id. (citing to cases from Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri).

[139] Unif. Prob. Code § 2-114(a).

[140] See id. at § 2-114(b). The UPC’s provisions, and many state behavior-based provisions barring inheritance, rely on “legal fictions” to both avoid unconstitutionality and to simplify application by courts. See, e.g. id. at §§ 2-114(b), 2-803(e). A “legal fiction” can be defined as “an assumption and acceptance of something as fact by a court,” regardless of truth in reality, “to allow a rule to operate or be applied in a manner . . . designed to achieve convenience, consistency, equity, or justice.” Legal Fiction, Cornell L. Sch. Legal Info. Inst., https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/legal_fiction (last visited May 9, 2024).

[141] See, e.g., Restatement (Third) of Property: Wills and Other Donative Transfers § 1.2.

[142] See Brown, supra note 20, at 547. See also Morey, supra note 21, at 798-99.

[143] Brown, supra note 20, at 551; Morey, supra note 21, at 798. A reasonable question to ask is what types of scenarios arise wherein an intestate child has an estate to inherit? One scenario involves wrongful death awards. North Carolina enacted America’s earliest unworthy parent statute in 1927 in response to the Supreme Court of North Carolina’s decision to give a “father who had abandoned his child” a “share in a wrongful death award when the child was killed by falling through an elevator shaft.” Brown, supra note 20, at 563–64 (citing Avery v. Brantley, 131 S.E. 721, 722-23 (N.C. 1926)). Another scenario involves adult children who predecease their parents without any other living heirs. In Washington state in 2001, an “unmarried and childless” adult man predeceased his biological mother whose parental rights had been terminated so that he may be adopted as a child. Id. at 583. Because the man was never adopted, and because a TPR statute prevented his biological mother from inheriting his estate, no legal takers existed and the estate escheated to the state. Id. at 583–84 (citing In re Estate of Fleming, 21 P.3d 281, 283–86 (Wash. 2001)).

[144] See Brown, supra note 20, at 551–52.

[145] See R.G. v. Marion Cnty. Off., Dept. of Fam. and Child., 647 L.E.2d 326, 330 (Ind. Ct. App. 1995).

[146] Id. at 327.

[147] Id.

[148] Id.

[149] Morey, supra note 21, at 799.

[150] In re A.V., 593 N.W.2d 720, 723 (Minn. Ct. App. 1999). “Palpably unfit” was a statutory standard defined as “a consistent pattern of specific conduct before the child or specific conditions directly relating to the parent and child relationship of a duration or nature rendering the parent unfit to parent for the foreseeable future.” Id. at 721 (internal quotations omitted).

[151] Id.

[152] Id. at 722.

[153] See Morey, supra note 21, at 799 (2017).

[154] Brown, supra note 21, at 569-77.

[155] Id. at 570.

[156] Id.

[157] See John H. Langbein, The Nonprobate Revolution and the Future of the Law of Succession, 97 Harv. L. Rev. 1108, 1108 (1984) [hereinafter Langbein]. See also Unif. Prob. Code art. II pref. note (including as a “theme” of the 1990 revisions “the recognition that will substitutes and other inter-vivos transfers have so proliferated that they now constitute a major, if not the major, form of wealth transmission”). See generally Beyer, supra note 3, at 267–321.

[158] Langbein, supra note 157, at 1108.

[159] Id. at 1120–21. Discharging the decedent’s debts is a central component of the probate process. See supra Section III. However, because the probate process only begins at the voluntary initiation by an interested party and often then relies on relatively primitive forms of accounting and notice, some creditors experience significant delay in receiving payments. Id. By tying debt to nonprobate instruments, creditors can avoid the entire probate hassle with self-executing documents. Id. at 1120–25.

[160] Id. at 1129.

[161] McCouch, supra note 17, at 758–59.

[162] “Inter vivos transfers” are “transfers from one living person to another.” Singer, supra note 6, at 148. These are to be distinguished from “testamentary transfers” which are “effectuated at death through a valid will or inheritance.” Id.

[163] Langbein, supra note 157, at 1140.

[164] McCouch, supra note 17, at 759.

[165] See e.g., id. at 758–60.

[166] See supra Section III.B.

[167] See supra Section IV.A.

[168] See supra Section IV.B.

[169] See Morey, supra note 21, at 800–02.

[170] See supra Section V.A.

[171] See supra Section V.A.

[172] See supra Section V.A.

[173] Brown, supra note 20, at 588–89.

[174] See supra Section V.B.

[175] See Brown, supra note 20, at 560.

[176] See supra Section V.C.

[177] See supra Section V.C.

[178] See supra Section V.C.

[179] For example, for a typical Louisiana probate to yield a net positive for the inheritor, the estate in probate would need to be worth at least approximately $8,000. See “How Much Does Probate Cost in Louisiana?” Smartasset (Jan. 30, 2024), https://smartasset.com/estate-planning/how-much-does-probate-cost-in-louisiana. This is because the average probate costs in Louisiana include: $300 in court filing fees, $3,500 in attorney fees, $1,000 in appraisal fees, $450 in notice publication fees, $150 in postage, copies, and notary fees, and 2.5% estate value in executor fees. Id. Moving to neighboring Texas, the estate being probated would have to be worth at least approximately $7,000. See “How much does it cost to probate a will in Texas?” Clearestate (Feb 3, 2023), https://www.clearestate.com/en-us/blog/the-cost-of-probate-in-texas. This is because the typical costs of probate in Texas include: $1,000 in administrative fees, a $325 court filing fee, $2,500 in accounting fees, $1,500 in inventory and appraisal fees, 2% estate value in personal representative fees, and 1% estate value in attorney fees. Id.

[180] See supra Section V.C.